How To Win War To Lose Peace

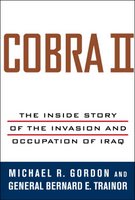

There have been numerous book published on the Iraq war, but Cobra II by Michael Gordon and Bernhard Trainor will be hard to beat.

There have been numerous book published on the Iraq war, but Cobra II by Michael Gordon and Bernhard Trainor will be hard to beat.It has already established itself as the most authoritative description of the preparation of the war and its actual conduct.

And it is certainly worth reading - both for the down-in-the-dust description of the usual fog and confusion that war always is, and for the insight in gives you on the miserable way in which one planned for the after-war situation.

According to the book, Donald Rumsfeld was as committed to fighting a new type of fast war with more limited quick-strike forces as he was determined that there should be no follow-up stability operations à la Balkans and definitely no so-called nation building.

Well, winning the war was undoubtedly a success, but peace has proved to be far more elusive.

And Cobra II gives at the least part of the answers why. There was litterally no planning for what to do after victory - apart from an astonishingly naive determination to withdraw US forces as fast as possible.

Only days after the fall of Baghdad in April 2003, preparations for leaving Iraq were ordered. General Franks flew into the city, meet the commanders that had fought their way to victory and said that they should be prepared to leave.

According to his guidance, the invasion force of 140 000 troops should be scaled back to about 30 000 troops by September. The belief was that there would be a functioning new Iraqi government up and running in thirty to sixty days.

Well, it didn't work out like that. The coalition forces in Iraq today are more numerous than the forces that won the war. In many respects they are still too few. And there still isn't a truly functioning Iraqi government.

Proper planning and far more numerous forces would certainly have avoided some of the worst of the mistakes, although it's an illusion that everything would have been smooth running without these obvious mistakes. But a difficult situation was undoubtedly made much worse and much more complicated.

But there are numerous other insights of value in the book.

There is the usual one on the difficulty of intelligence. It turns out not only that the US intelligence assessments were wrong on the issue on weapons of mass destruction, they were also substantially wrong on what the US forces would encounter once they entered the country.

There is seldom such a thing as certainty when it comes to intelligence. The Iraq war certainly illustrated that old thruth again.

A book well worth reading.

<< Home