The Legacy of Olof Palme

These days it is 20 years since Prime Minister Olof Palme was murdered a dark night on the streets of Stockholm.

He was a person of controversy, and his policies were not universally admired. But he was a man of immense talents, intense energy and an international outlook that has to be admired to this day.

His murder was a national trauma that to some extent continues to this day.

His legacy in domestic politics remains somewhat doubtful. He become leader of the Social Democratic Party in 1969, and was convinced that he had to ride the leftist wave that dominated those years.

This lead not only to a loss of voters in the 1970, 1973 and 1976 elections, when he had to hand over to the centre-right coalition government under Thorbjörn Fälldin. Economic policy also started to stray seriously, with a substantial rise in the tax burden, new regulations and a catastrophic loss of competitiveness for industry.

It was in the mid-70’s that Palme – as part of a scheme to take what he said was the third and final step in the building of a democratic socialist society – launched the scheme of the so-called wage-earners fund.

In essence, business should pay for their ownership being transferred to the trade unions. It was certainly socialist, and threatened the very foundations of society.

It wasn’t the first time in its history that the Social Democrats, under the influence of the mood of the times, had tried more radical socialist measures. But in much the same way as with the previous attempts in 1928 and 1948 it backfired.

Although the issue was with Palme in the subsequent elections he fought in 1979, 1982 and 1985, the last remnant of the funds were abolished as one of the very first steps of the now centre-right government in 1991, and they have not been heard of since then.

It’s an issue no modern Social Democrat dares to revive. It had lead them into a blind alley.

But those were the days when half of Europe claimed to be socialist, and Palme used to say that he pursued a policy of a third way between capitalism and communism.

The problem is that this policy – apart from its economic mistakes – also had a tendency to devolve into a policy of third way between democracy and dictatorship.

He hailed friendship and solidarity with Fidel Castro and other revolutionary regimes in the Third World. These were the years of a certain romanticism concerning the revolutions in the developing countries, and Palme wanted to be in the forefront of that movement.

The Vietnam war is an integral part of that story. It radicalised a generation at the least in Europe. And Palme was right in saying that it wasn't a question of a Sinosoviet conspiracy trying to conquer the world, and that the national element in Vietnam was strong.

But he was certainly wrong in portraying it as a war for liberation and democracy in Saigon - we now know it ended with a communist dictatorship imposed from Hanoi. And he outraged also many Americans critical of the war by comparing aspects of US policy with the worst atrocities of Hitler. There were many who had not forgotten - perhaps not even forgiven - that in the fight against Hitler Sweden had been neutral.

But it was in his attitude towards the socialist systems of the Soviet empire that he in the end ran into the gravest difficulties.

He could occasionally be harshly critical of manifestations of repressive policies in Eastern Europe, but he was adamant that the Soviet system as such must not be called into question. And he fought fierce political battles against those in Sweden - me included - that dared to say that freedom and democracy in Eastern Europe was a precondition for true peace in all of Europe.

At his last party congress in 1985, he firmly said that there was no room for being anti-Soviet in his or his party’s policies. And already in 1970, he had denied Alexander Solsjenitsyn access to the Swedish Embassy in Moscow after Solsjenitsyn - to the immense displeasure of the Kremlin - had been awarded the Nobel Price in Literature.

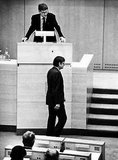

This is where he and I most clearly parted ways. The picture is from a well-known parliamentary encounter centered exactly on those issues.

One could not claim to be a “moral superpower” if that morality was only applied to one part of the world, but descended into silence on what was happening just across the Baltic Sea. It was a one-eyed policy, and as such it was neither credible nor moral.

His brutal murder on that dark February night in 1986 changed the politics of Sweden. In spite of everything, there is no doubt that he left a void. For all of the verbal excesses, all of the mistakes and all of the perverted perspective - there was a luster over his days.

Today, we live in a profoundly different world.

Much of what he fought against on the Swedish domestic scene has happened. Parents are free to choose their own day-care center – this was an idea he fought with the full force of his rhetoric.

The revolutionary regimes in the Third World brought mainly misery to their peoples. It’s those abandoning socialist policies that are doing best today. And the Soviet Union is gone. There is no longer any wall in Berlin.

His world was a different one. We have moved on.